Since its introduction in 2015, the Rule of 40 has gained significant traction amongst venture capitalists and stock market observers.. This metric can provide a quick assessment of whether a SaaS company’s business model is effective.

The Rule of 40 is a mathematical expression of an idea originally featured in Brad Feld’s post: “We can become profitable right away if we slow our growth rate.” It underscores the feasibility of a SaaS company to trade growth for profitability.

As the economy slows, interest rates rise, and investors focus more on cash flows, the Rule of 40 is facing its first real test. Instead of purely emphasizing aggressive growth at the expense of profitability, maintaining a healthy balance between the two is now crucial.

This article explores the Rule of 40, how it’s calculated, when it can be applied, and its relevance in the current economic environment.

Summary

- The Rule of 40 is a simple way to assess a SaaS company’s performance. This rule states that a SaaS company is healthy if the sum of its revenue growth and profitability margin (EBITDA, EBIT, or free cash flow) is higher than 40%.

- The Rule of 40 should only be applied to companies employing SaaS/software subscription-based business models. It’s not suitable for analyzing marketplaces, e-commerce, or other non-software companies.

- Inflation can make it easier for companies to pass the Rule of 40, especially those that perform well on cost pass-through using simple price hikes.

- With the global economy slowing down and interest rates increasing, companies are now prioritizing profitability over revenue growth. The Rule of 40 remains useful, but now demands positive performance for both growth and profitability.

What is the Rule of 40?

The Rule of 40 is a metric used to assess the performance of a SaaS company. According to this rule, a SaaS company is considered healthy when the sum of its revenue growth rate and profitability margin exceed 40%. The rule implies a trade-off between growth and profitability, suggesting that the former can be traded for the latter.

In essence:

- If a company’s revenues grow at 30% year-on-year, it should have a profitability margin of at least 10%.

- If a company’s growth is 60% year-on-year, it can sustain a profit margin of negative 20%, i.e. a loss.

Initially introduced as a quick way of assessing a company’s health, the Rule of 40 has evolved into a widely used metric for evaluating listed SaaS companies’ performance. In this context, a higher Rule of 40 number might suggest a more effective company.

Calculating the Rule of 40

To calculate the Rule of 40, you must first assess a company’s revenue growth rate and its profitability margin. Once these two metrics have been found, you can add them together to evaluate a company’s ‘health’ in line with the Rule of 40.

Below, we outline how to calculate a business’s revenue growth rate and profitability margin.

Revenue growth

There are several different ways to calculate a business’s growth rate.

The most common approach for calculating SaaS business growth is to take the year-over-year change in MRR (monthly recurring revenue) or ARR (annual recurring revenue). This method is most fitting for SaaS companies as it primarily includes recurring revenues.

Another way to measure annual revenue growth is to use total revenue as reported in the financial statements. Unlike ARR/MRR, total revenue includes income from non-recurring sources (e.g. one-off professional services or lifetime subscriptions). However, this metric may not be accurate if a company has a significant share of non-recurring revenues.

Companies often have different accounting policies which can impact revenue recognition. While some smaller companies may recognize revenue based on cash billings (as the point of sale), a correct calculation of the Rule of 40 requires accrual accounting. This allows revenue to be recognized over the duration of the client’s contract, providing a more accurate picture of when the company earns its revenue.

Profitability margin

Numerous methods exist to determine a company’s profitability margin. The most common are the EBITDA margin, operating profit margin (EBIT margin), and free cash flow margin (FCF margin).

The EBITDA margin is a popular profitability metric that should be used with caution. This is because it can be influenced by aggressive capitalization of development costs, leading to an increase in depreciation add-back. In these situations, using the EBIT margin instead of EBITDA may offer a clearer picture.

Another way to measure a company’s profitability is using the FCF margin. This is calculated by dividing a company’s free cash flow by its sales for a period. It’s essential to be consistent in calculating FCF, as there are various ways to do this.Analysts will typically adjust the EBITDA for capital expenditure, share-based compensation, and net working capital when using the FCF formula.

The argument for using FCF margin is that it provides insight into a company’s cash generation potential. Unlike EBITDA, free cash flow considers CAPEX, so capitalization of development costs is irrelevant. It also factors in net working capital, accounting for the fact that SaaS companies sell long-term subscriptions and recognize revenue over time, despite receiving cash in advance.

Whether using EBITDA, EBIT, or FCF margins, it’s important to factor in share-based compensation (SBC). Because SBC is included in the calculation of free cash flow as an add-back, some argue that it’s a cashless expense similar to depreciation and amortization. However, it dilutes the shares of other shareholders and leaves them with a smaller fraction of ownership.

If a company wants to avoid diluting existing shareholders, it will have to use cash to buy back shares on the open market. This means that ultimately, although the payment is non-cash, SBC is still recorded as an expense on P&L statements and can significantly impact the Rule of 40 assessment.

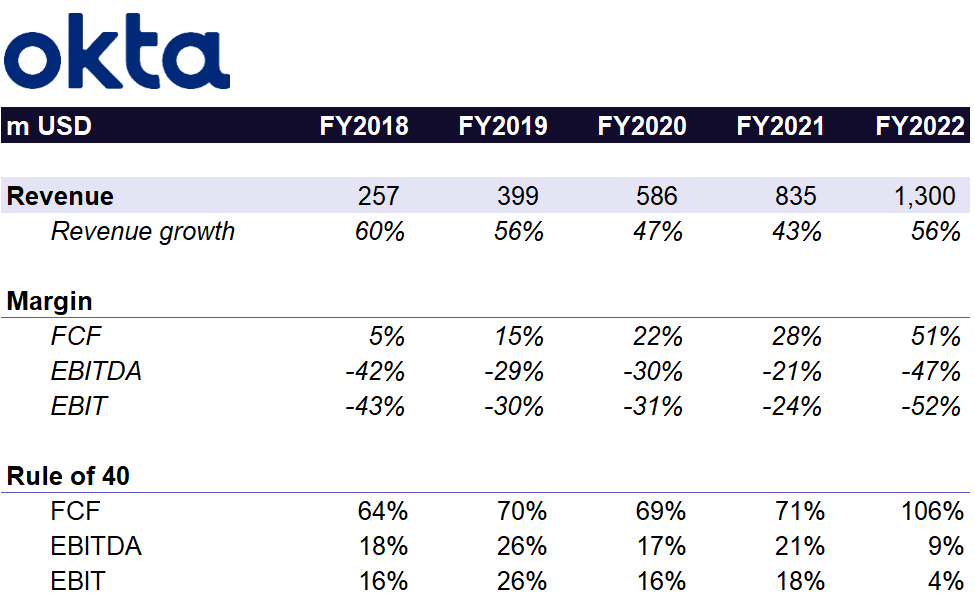

For example, Okta paid its staff more than $560M in stock-based compensation in FY2022. Combined with other non-cash expenses and cash received early from customers, there is a staggering difference between the 51% FCF and the -47% EBITDA margin. This large difference is the result of adding back the $560M in stock-based compensation to FCF, but not to EBITDA. Again, since Okta has a significant stock-based compensation that will eventually turn into an expense for the company, it’s not adjusted for in EBITDA.

Analysts tend to avoid adjusting for significant and recurring SBC, however maintaining a consistent approach is more important than which method is chosen.

There’s no right answer when it comes to which profitability margin to use. For most SaaS and software companies, these metrics will yield similar results, especially when using adjusted figures. The key is to decide on the most relevant method for your business/industry and compare metrics consistently.

When to use the Rule of 40?

Industry and business model

Initially conceived for SaaS companies, the Rule of 40 has become a popular rule of thumb for all software companies. It’s most suitable for companies with a subscription-based business model.

Our view is that the Rule of 40 is a relevant metric when a company’s business model incorporates a trade-off between current profitability and future growth: The first option is to prioritize immediate profitability by spending less on customer acquisition, potentially curbing future growth. The other choice is to ‘compromise’ current profitability by spending heavily on growth initiatives and customer acquisition.

The Rule of 40 clearly illuminates how profitability can be temporarily sacrificed for growth. However, for a loss-generating business with no prospects of becoming profitable, the Rule of 40 holds little value.

Company size and phase of the business cycle

In his original post, Brad Feld writes that the Rule of 40 is best used for companies at scale with $50M in ARR. In general, this revenue target is met by well-established mature companies. However, even companies with $10M in ARR can benefit from the Rule of 40. Instead of focusing on size, it’s better to look at the stage of the company’s business life cycle.

Notably, early-stage companies experiencing rapid growth from smaller bases, often with hundreds of percent growth rates, aren’t ideal candidates for the Rule of 40. These companies should focus on product-market fit, generating initial revenue, and serving existing customers. The Rule of 40 may be a good guideline for more established companies, but it doesn’t apply to start-ups in early stages of development.

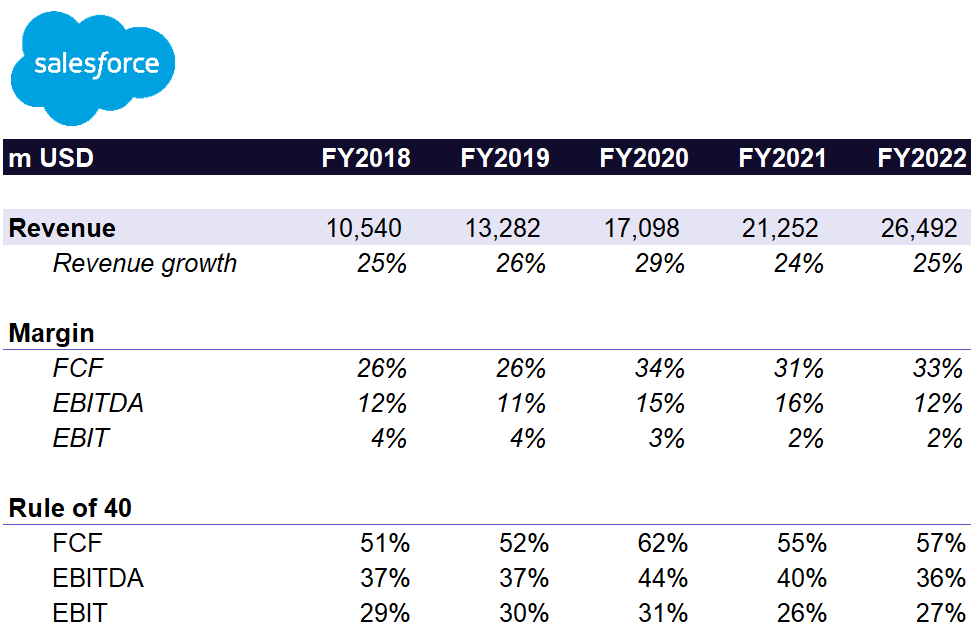

On the other hand, the Rule of 40 can be well applied to mature businesses. For example, Salesforce, one of the pioneers of the SaaS business model, has delivered high growth at around 25% with 10-15% EBITDA margins, despite reaching significant scale. The caveat, however, is that a large portion of Salesforce’s growth is inorganic, coming from a significant number of acquisitions.

When not to use the Rule of 40?

The Rule of 40 was initially created to analyze SaaS companies, as it works best with subscription-based business models. However, it’s now used for all kinds of business models, often to justify massive losses based on revenue growth.

For example, it makes little sense to use the Rule of 40 for eCommerce companies, as their business model relies on selling lower-margin third-party manufactured goods and services, which is different from selling proprietary software. Over the long term, these companies can typically achieve only a low-single-digit EBITDA margin. To be considered healthy according to the Rule of 40, these companies need to grow above 30% in perpetuity. Additionally, lower customer retention and LTV in eCommerce purchases make the trade-off between growth and profitability much less obvious.

How does the Rule of 40 influence valuation?

The Rule of 40 significantly influences the valuations of Software as a Service (SaaS) companies, serving as a crucial indicator of a company’s operational efficiency and growth potential.

In the realm of SaaS businesses, the revenue multiple is among the most widely employed valuation metrics. In our analysis, we focused on how the Rule of 40 correlates with the revenue multiple across 70+ companies from our SaaS Index.

As a rule of thumb, a 10% increase in the Rule of 40 score typically corresponds to around a 0.8x growth in the revenue multiple. In simpler terms, when a SaaS company exceeds the Rule of 40, demonstrating a balance between growth and profitability, investors tend to assign a higher valuation. This is based on the expectation of sustained growth and operational efficiency.

A deeper analysis indicated that it’s primarily the growth element of the Rule of 40 that accounts for the difference in revenue multiple for listed companies.

Is Rule of 40 still relevant?

The first test of the Rule of 40

Created in 2015, the Rule of 40 emerged during times of unprecedented economic and stock market growth. Ample venture capital funding allowed tech companies to invest aggressively in growth and building a customer base. Many companies showed efficiency in meeting the Rule of 40 criteria, primarily due to extraordinary sales growth rates.

Software companies with solid profitability margins were more common among names founded in the past century – Adobe, Salesforce, Intuit, and OpenText – supporting the premise that, if one waits long enough, profits will come.

However, as SaaS businesses mature, the economy slows down, and interest rates rise, the premise of the Rule of 40 will face its first major test. Can companies genuinely choose between profitability and growth? Is 40% profitability at a 0% growth rate as achievable as reaching 40% growth with no profitability margin?

Growth slowdown

As MRR growth declines, SaaS companies are expected to reap the benefits of past exponential growth and transform it into solid profitability margins.

Several companies have reported strong SaaS metrics like high LTV/CAC, low churn, and 100%+ net revenue retention, suggesting that growth can continue even with less investment.

Companies reaching a sustainable growth of 10-20% a year are required to achieve 20-30% profitability margins to be considered efficient. The next few years will reveal whether exchanging growth rates for profit is as feasible in reality as it is in a spreadsheet.

Inflation and the Rule of 40

Inflation can have a significant impact on the Rule of 40. If inflation is high, companies need to increase their prices to maintain profitability margins. While many countries report inflation close to 10%, some emerging markets are experiencing price surges above 20%.

Companies that can effectively pass on higher costs to consumers (protect margins), will more easily reach the 40% target through simple price hikes. Therefore, if CPI remains at around 10%, then the rule could be adjusted to 50% or higher. Either way, it’s important to monitor inflation when assessing a company’s performance using the Rule of 40.

Focus on profitability

Rising interest rates devalue future cash flows for investors, impacting SaaS strategies that rely on a large upfront investment to acquire customers, eventually generating cash years down the line. With higher discount rates, the present value of future customers is lower, meaning a company needs more time to become profitable.

At the same time, some aspects of SaaS businesses are becoming less appealing. For example, long-term contracts without price indexation are less attractive in times of rapid inflation.

The future of the Rule of 40

Originally a valuable tool to identify healthy businesses in times of boom, the Rule of 40 may become overly lax to rapidly-growing companies with low profitability margins or high churn.

One way to improve the analysis is to apply a Weighted Rule of 40, emphasizing profitability over growth by assigning more weight to profitability margins than to a company’s growth rate. For example, using a 1.33 weight for profitability margin and 0.67 weight for revenue growth.

In any case, balancing growth and profit will remain a high priority for founders. The current environment suggests companies must sacrifice growth for a quicker path to profitability, necessitating a positive outcome for both components of the Rule of 40. However, it’s becoming increasingly difficult to argue that mature SaaS businesses losing 20% a year while achieving 60% yearly revenue growth are healthy.

Rule of X – An Alternative to Rule of 40?

In December of 2023, a new and modified metric was proposed by Bessemer Venture Partners called Rule of X.

So, what is Rule of X? It is a revised version of Rule of 40 that suggests growth is more valuable for a SaaS business than profitability. The Rule of X allocates a minimum 2-3x multiplier to the growth rate, so instead of the traditional (Growth + Profitability Margin) formula, the Rule of X = (Growth x Growth multiplier) + Profitability Margin.

The Rule of X seems to explain better the variation in the valuation of SaaS companies, suggesting that public market investors indeed price growth 2-3x more than profitability. During the “Growth at all costs” era, investors valued growth as much as 9 times more.

Still founders of thousands of smaller private SaaS companies optimize for the long-term development and success of the company, not for the current stock market valuation. That is why we would caution from using the Rule of X framework where it doesn’t apply. In our view, founders can sacrifice some growth in order to reach profitability, especially when financing is scarce and the next round is not a given.

Why you need a SaaS M&A advisor

Understanding SaaS valuation dynamics offers valuable insights into the factors influencing your business’s valuation and can help in effectively time your exit strategy. Each SaaS company is unique, just like every founder’s journey. Consulting with experts in the SaaS M&A landscape, especially advisors who specialize in the sector and understand your circumstances, will highly enhance the change of a successful sale process.

SaaS M&A advisors understand how to navigate market dynamics, valuations, and coordinate all the necessary workstreams. While you concentrate on running your business, SaaS M&A advisors work diligently to ensure that no detail is overlooked and advocate for the best possible deal. Their success is directly linked to yours through a success fee structure, and their influence on the final sale price can therefore be substantial.

About Aventis Advisors

Aventis Advisors is an M&A advisor for SaaS companies. We believe the world would be better off with fewer (but better quality) M&A deals done at the right moment for the company and its owners. Our goal is to provide honest, insight-driven advice, clearly laying out all the options for our clients – including the one to keep the status quo.

Get in touch with us to discuss how much your business could be worth and how the process looks.