In today’s dynamic technology landscape, valuing software companies is both an art and a science for entrepreneurs and investors alike. These coveted gems warrant meticulous valuation, and although no perfect formula exists, using proven methodologies can help provide a solid approximation of a software company’s value.

In this blog post, we discuss two prevalent valuation methodologies: income-based and market-based approaches. While other valuation methods exist, such as the asset-based approach method, they’re rarely used in the context of software companies. For that reason, we won’t be discussing them in this blog post.

Use cases of company valuation

Before you begin to value a software company, it’s crucial to understand why this exercise is so important. Understanding a software company’s value has several practical implications that can benefit your company in many ways. These include:

- Selling your company: Gaining an accurate valuation is vital when selling your software business and helps you secure the maximum price. By understanding your firm’s valuation and drivers, you can take the right steps to optimize the company’s value before entering the sale process.

- Secure investment and financing: When seeking external funding (e.g. venture capital or private equity), having a clear understanding of your software company’s value will significantly benefit negotiations, increasing your chances of securing the necessary capital.

- Expanding your business: When pursuing significant growth, whether through organic means or M&A, it’s crucial to first establish your firm’s baseline value. This valuation serves as a benchmark, allowing you to assess the impact of strategic moves on your company’s value over time.

Software company valuation methods

There are two main methods used to value software companies:

- Income approach: This method involves performing a discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis to estimate value based on expected future earnings.

- Market approach: This method derives a company’s worth by examining valuation multiples from comparable public entities or M&A deals.

Both of these approaches have pros and cons. Choosing the right approach is usually determined by the purpose of the valuation and the analyzed software company’s financials and operations.

Below is a detailed example of how both of these approaches work.

Income-based approach

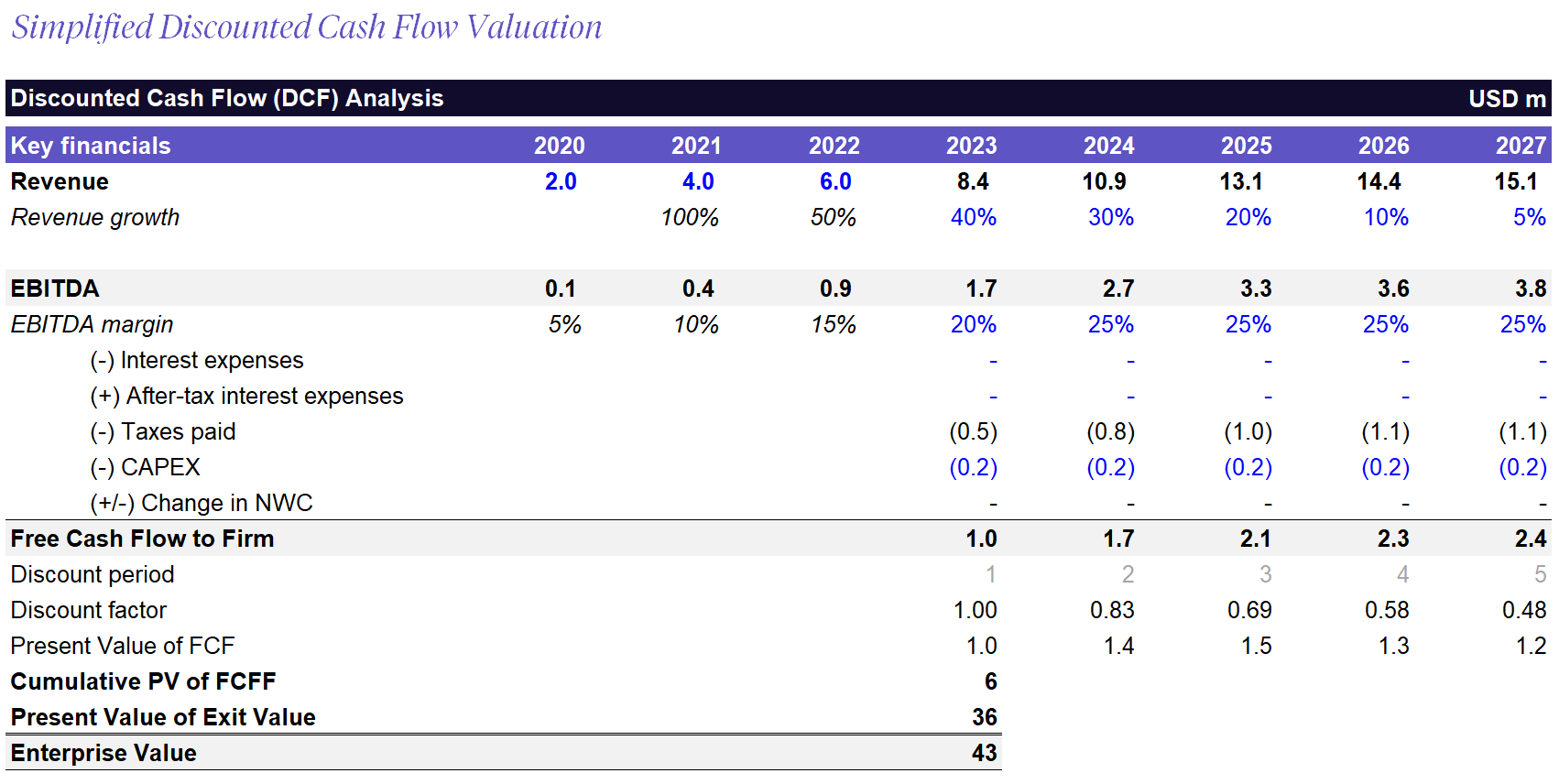

The income-based approach follows the discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis to value a software company based on its future free cash flows.

The first step in the DCF is to create a detailed financial model projecting typical revenue growth, expenses, capital expenditures, and working capital for the next 3-5 years. These projections may stem from management guidance, historical performance, or an estimation of the company and market’s future trajectory.A stable growth rate is assumed beyond the projected period, known as the terminal growth rate.

The financial projections can be used to calculate the expected future cash flows of the software company. These cash flows are then discounted at a rate reflecting the company’s capital cost or the investor’s required return, depending on the valuation’s purpose. This discount rate may be adjusted to account for various other factors, such as political, economic, ownership, and business continuity (e.g. start-up) risks. Discounting the cash flows results in the enterprise value of the software company. This represents the company’s valuation and present value..

In the context of M&A, it’s important to distinguish between enterprise value and equity value. If you’re selling your software business, the amount received will be the equity value. This is derived from the enterprise value after adjusting for net debt, normalized working capital, preferred shares, and minority ownership (if any).

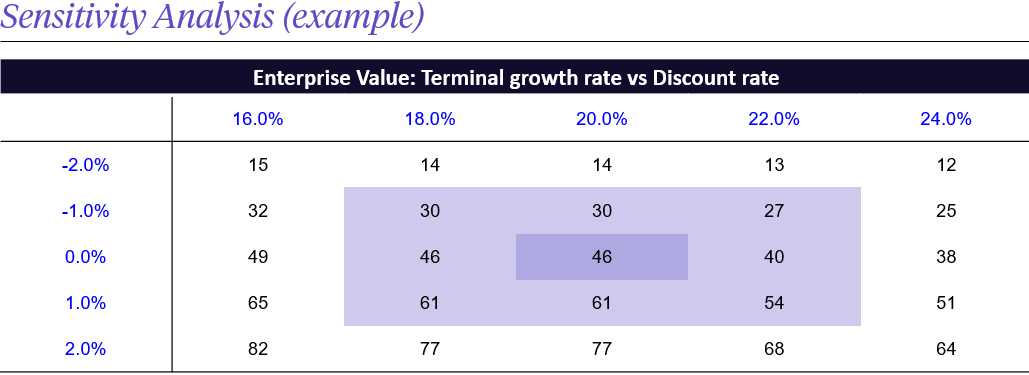

After completing DCF modeling, we can conduct a sensitivity analysis. This assesses the impact of alterations in crucial assumptions (such as discount and terminal growth rates) on the valuation outcome. A sensitivity analysis helps understand the range of potential values and how the valuation model responds to different variables.

Pros and cons of the income-based approach

There are many advantages to using the income approach, or the Discounted Cash Flow method, to ascertain the value of software companies. These include:

- Cash Flow Focus: DCF considers a company’s projected future cash flows, providing a detailed examination of its revenue streams and financial performance.

- Flexibility: DCF can incorporate changes in growth rates, discount rates, and terminal values. This accommodates the dynamic nature of the software industry and its potential for rapid shifts.

- Intrinsic Value: DCF aims to estimate the intrinsic value of a company. This aligns well with assessing software companies that might have intangible assets, such as IP, brand, or user base, as key value drivers.

- Long-Term Perspective: DCF emphasizes a long-term view of a company’s value. This aligns with the nature of software companies that often invest heavily upfront for future returns.

Despite its numerous benefits, the DCF method also comes with its own limitations, which must be factored in. These include:

- Uncertain Projections: Accurate forecasting of cash flows can be challenging in the fast-changing software industry. The software sector is known for its rapid innovation and evolving market conditions, making future growth rates and conditions highly uncertain.

- Sensitivity to Assumptions: DCF is highly sensitive to assumptions like growth rates and discount rates. Small changes in these inputs can lead to significant changes in the calculated value.

- Inadequate for Rapidly Growing Firms: DCF’s terminal value calculation might not adequately capture the potential for rapid growth in software companies. This is because it assumes perpetual cash flows beyond the forecast period.

- Neglects Market Sentiment: DCF doesn’t explicitly consider market sentiment, which can heavily influence software company valuations. This is especially the case in sectors driven by hype and innovation.

- Complexity: DCF analysis involves intricate calculations, which make it the most complex valuation method in most cases.

While DCF is a valuable tool for valuing mature software companies with stable growth and profitability, investors often prefer more straightforward multiples methods, such as using DCF results to derive revenue or EBITDA multiples. DCF’s primary value lies in understanding the drivers of a company’s value and illustrating which metrics affect valuation the most.

Market-based approach

Valuation multiples are commonly used to benchmark a company’s value against a selected financial metric. For public companies, equity multiples, such as share price to earnings and book value, are commonly used.. For private software companies, enterprise value multiples such as EV/EBITDA and EV/Revenue are popular with analysts and investors.

The EBITDA and Revenue multiple

The EBITDA multiple is often favored for enterprise valuation. This is because it is independent of a company’s capital structure, making it suitable for comparing companies with varying debt levels. It also focuses on genuine cash generation irrespective of accounting decisions.

Although the EBITDA multiple is so commonly used, there are situations where alternative multiples are a better option. The most common alternative is the revenue multiple, which works well with start-ups or companies with negative cash flow and net income.

In some cases, other multiples like EBIT may be more suitable. For example, EBIT can be used for industries with substantial depreciation and amortization, such as the asset-heavy industrials and energy sectors.

Finding the multiple

After selecting the financial metric we want to multiply (revenue, EBITDA, EBIT, etc.), the next step is to calculate the multiple. The two most common sources of comparable multiples are publicly traded companies and precedent transactions.

Comparable company analysis

This method involves analyzing the median or mean EBITDA multiple within your business’s industry or peer set. It requires extensive industry insight and research to identify suitable peer companies. Further adjustments may be required to align the resultant EBITDA multiple with variations in characteristics and operations.

Precedent M&A transactions

This approach is employed primarily in M&A deals and looks at valuation multiples from past transactions that are relevant to your business. This method relies on having access to recent transactions among businesses similar in size and scope to your software company. It’s important to note that adjustments may be required to account for premiums paid for potential synergies.

M&A in the Software Industry

Historical EBITDA Multiple Analysis

While less common than the above two methods, this approach involves reviewing your business’s past EBITDA multiples for a quick current value estimate. Historical multiples can be obtained from financing rounds with venture capital and private equity firms. However, adjustments remain necessary to address significant industry shifts and changes in your company’s attributes and operations.

Pros and cons of the market-based approach

There are many benefits to using valuation multiples to determine a business’s value. Some of these advantages include:

- Simplicity: Valuation multiples are simple to calculate and interpret, making them a preferred choice among financial experts for quick, back-of-the-envelope valuations.

- Flexibility: These multiples can be tailored to specific sectors by choosing appropriate numerator and denominator combinations, resulting in industry-specific ratios.

- Comparative analysis: Multiples analysis allows you to compare your software company’s value with its peers. This insight highlights whether competitors are valued at a premium or a discount relative to your business.

- Market-driven: Multiples reflect the market’s perception of value, providing insight into investors’ potential willingness to pay for your business.

Like DCF analysis, using the market-based approach also comes with its own limitations. These include:

- Simplistic approach: While the straightforward nature of valuation multiples can be an advantage, it also poses limitations. This method overlooks various factors influencing a company’s value, such as management quality or business model.

- Limited comparable data: Businesses in niche sectors may have a small peer group, making it difficult to draw meaningful conclusions about median or mean valuation multiples. Data on private company valuation multiples can also be scarce. In the context of M&A, the scarcity of prior transactions might result in an unreliable benchmark for valuation.

- Subjectivity: Valuation multiples involve subjective assumptions, such as defining the peer group and adjusting for differences in attributes and operations. Consequently, different interpretations of these elements can lead to divergent calculated values.

Software Valuation Multiples: 2015-2023

Additional metrics affecting software company valuation

It’s crucial when valuing a software company to consider various industry-specific financial metrics that can significantly affect its worth. With SaaS companies, for example, a broad spectrum of metrics can be used to improve valuations, including customer acquisition cost, lifetime value, net retention rate, and ARR.

It’s also important when valuing a software company to examine its various revenue sources. Subscription and license revenues are usually considered the most valuable as they demonstrate consistent customer commitment and are linked to core product offerings. On the other hand, revenue from implementation and maintenance, though significant, may hold a relatively lower valuation. This is because they often consist of one-time or periodic services that support primary software utilization.

Another crucial consideration is how Research and Development (R&D) expenses are handled. By US GAAP, generally, all R&D costs are immediately expensed, except in cases involving capitalized software costs and motion picture development. On the other hand, IFRS follows a similar path of expensing research costs but introduces the possibility of capitalizing development costs, provided specific criteria are met.

Other metrics and factors that can affect valuation but aren’t specific to the software industry include:

- Market Trends: Stay up-to-date with current market trends and industry developments that could impact your software company’s growth prospects.

- Intellectual Property: Assess the value of your company’s intellectual property, such as patents, copyrights, and proprietary technology.

- Customer Base: Examine the size, loyalty, and diversity of your customer base, as well as the company’s ability to retain and expand its customer relationships.

- Synergies with the buyer (in case of an M&A): A strategic buyer can unlock substantial synergies, such as cost savings and technological advancements. These buyers may offer a higher price than those who may not reap these synergistic benefits.

- Competition for a deal (in case of an M&A): Multiple buyers competing for a company create a competitive environment that can drive up prices. On the other hand, a lone buyer may have more negotiation leverage.

While it may seem straightforward to obtain a ballpark valuation, it’s important to consult with experts, such as M&A advisors, when making significant financial decisions, especially during the sale of your business. Their guidance and expertise can help ensure you receive appropriate compensation for your company’s value.

Why you need a Software M&A advisor

Keeping track of software valuations offers insights into market trends and aids in timing your exit strategy. However, each company is unique, just like every founder’s journey. For this reason, it’s essential to seek guidance from experts in the M&A space, particularly software M&A advisors who specialize in your industry.

Software M&A advisors are well-versed in navigating market dynamics, understanding valuations, and coordinating all necessary workstreams. While you concentrate on running your business, software M&A advisors diligently ensure that no detail is overlooked and advocate for the best possible deal. Their success is directly linked to yours, and their influence on the final sale price can be substantial.

About Aventis Advisors

Aventis Advisors is an M&A advisor for software companies. We believe the world would be better off with fewer (but better quality) M&A deals done at the right moment for the company and its owners. Our goal is to provide honest, insight-driven advice, clearly laying out all the options for our clients – including the one to keep the status quo.

Get in touch with us to discuss how much your business could be worth and how the process looks.